Mass Arrival (2013) is a public art, installation and new media project, conceived of by Farrah Miranda. Preferring to work collectively, Miranda formed the Mass Arrival Collective: Farrah Miranda (artist) Graciela Flores-Mendez (legal worker), Tings Chak (artist-architect), Vino Shanmuganathan (law student), Nadia Saad (social worker). The project has been presented in solo and group exhibitions at Whippersnapper Gallery (Toronto), Surrey Art Gallery (Surrey), Astérides (Marseille), has received the generous Ontario Art Council support.

Juxtaposing visual and textual narratives surrounding migrant boat arrivals to Turtle Island (Canada), it becomes clear that while some white arrivals form the basis of national creation stories, others form the basis for fear, hysteria and the tightening of border control.

1492: Boats carrying white-European settlers pulled up to the shores of Turtle Island (North America. A war was waged against the original Indigenous inhabitants of this land. The legacy of this war is birthed in claims to racial and moral superiority and enclosed in borders. Creatively naming themselves as pioneers and explorers, white settlers imposed a logic of race based entitlement that till today leaps from the pages of textbooks.

1914: A ship carrying 476 mostly Punjabi passengers from British controlled India arrived at the shores of Coast Salish Territories, (British Columbia). The passengers, British subjects, were challenging the Continuous Passage regulation, which stated that, “immigrants must come from the country of their birth, or citizenship, by a continuous journey, and or through tickets purchased before leaving the country of their birth, or citizenship”, a law brought to curb immigration from India.

1939: Sailing from Hamburg with 907 Jewish refugees on board, the St. Louis, sought safety in Canada, among other places in the Americas. Racialized and rejected, the migrants were returned to Europe where most of its passengers died in the Holocaust.

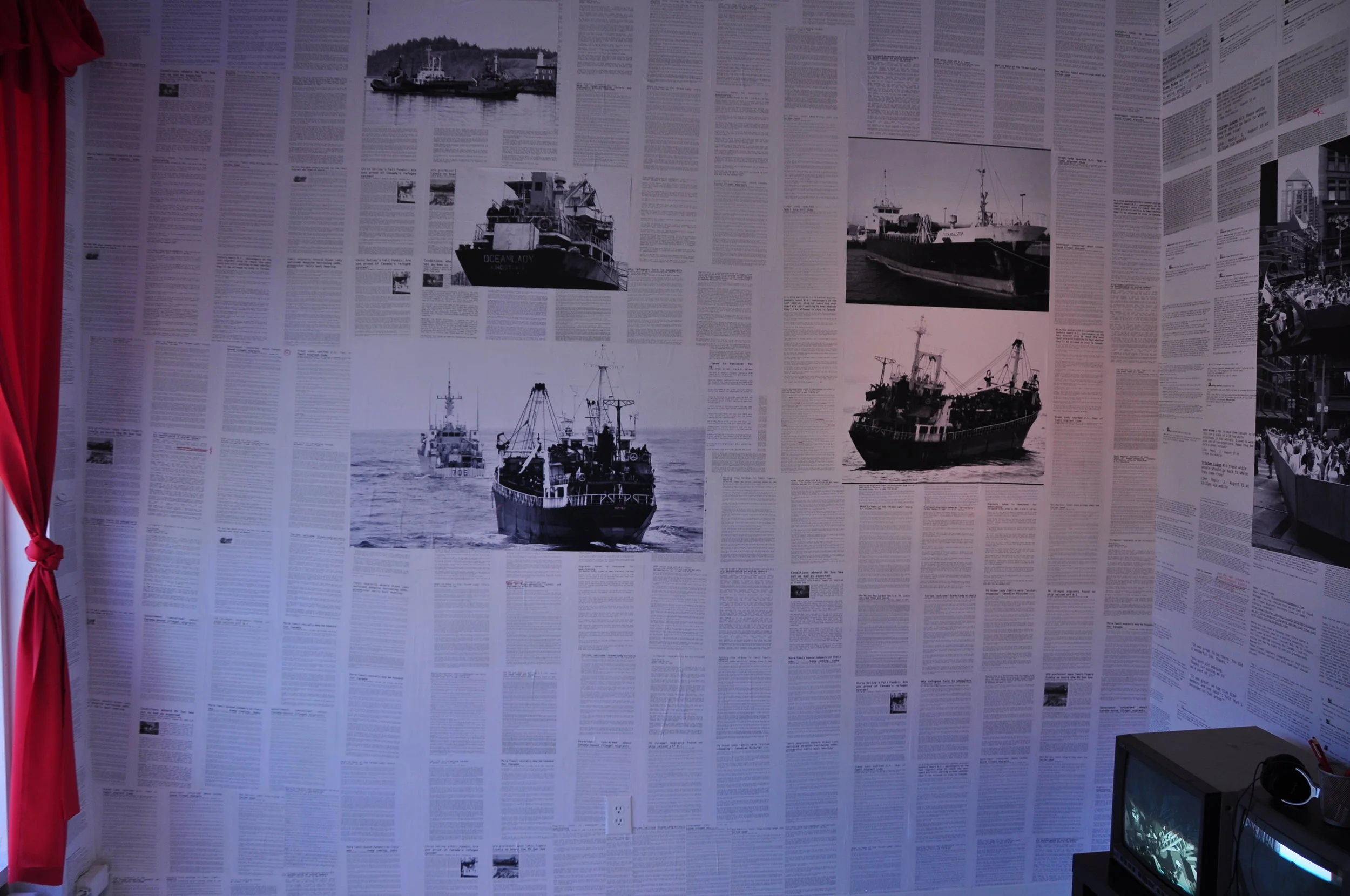

1999: Four separate ships carrying 599 migrants from the Fujian province of China arrived at the shores of Coast Salish Territories (British Columbia). Met with national disdain, the migrants aboard these ships were cast with immense suspicion. Highly visibilized and characterized as illegal boat people, the migrants aboard these ships were cast as a threat to Canadian sovereignty, and fore-fronted as a symbol of Canada’s failing refugee policy.

2009 & 2010: Freighter ships, the MV Ocean Lady, carrying 76 Tamil migrant men was seized off the shores of Coast Salish Territories (British Columbia). Less than a year later the MV Ocean Lady landed ashore in Canada, this time with 492 Tamil passengers. Prior to its arrival, an online survey of about 1,000 Canadians found that 48% of those polled would deport the passengers from the Sun Sea, even if their refugee claims were found to be legitimate, with and no links found between the migrant and a terrorist organization. Thirty-five per cent of those surveyed would allow them to stay in Canada as refugees if their claims are found legitimate (Fong, 2010).

2013: Mass Arrival docked a ship built of canvas and plywood, filled it over 200 white people, and docked it in a busy Toronto intersection. This intervention marked the third anniversary of arrival of 492 Tamil migrants aboard the MV Sun Sea.

Emanate from these contexts are themes of visibility and invisibility; themes of historical erasure and assertion; and the question, who has the moral legitimacy to decide who belongs in a settler colonial nation state.